Google and Mary Anning galvanized me to get back on the horse and explore my idea that certain long necked plesiosaurs may have routinely used rotational feeding to dismember large carcasses and literally wrench hapless ammonites from the safety of their shells. If you want to review here. I had considered making a paper out of this topic, but it may be a little too out there for proper scientific journals. But then again I think my idea has as much merit as any other suggestions for plesiosauromorph feeding ecology.

Now here I want to qualify my thoughts on this hypothesis as such, since I have changed my views a bit: Maybe I went a tad bit too far suggesting ammonites were the primary impetus in plesiosaurs evolving long necks. I think I may have overstated my claim a bit there - but I do maintain that the long neck conferred advantages that compensated for the disadvantages it had. And the chief advantage being a stealthy approach to prey without the prey sensing the pressure wave of the plesiosaur. But here I do not think I differ too much with what most think anyways.

Secondly not all plesiosaurs were ammonite predators and some were doing completely different stuff such as infaunal sifting or maybe even some type of filtering of small prey from the water column. I do not want to propose a one size fits all approach to these guys.

But I do believe there is some compelling arguments to make counter to the prevailing notion that plesiosauromorphs were gape-limited specialists of small prey. Although not suggesting that they were arch-predators on the order of giant pliosaurs or mosasaurs I will argue that many plesiosauromorphs could take and dismember prey a lot larger than generally portrayed.

I hope to do a series of posts exploring this idea and as always would love feedback in the comments section. One word on comments though, please put your comments on the blog and not on facebook- you do not need to sign in or get a google account anymore. When you comment on facebook and leave insightful or intelligent stuff - it goes away eventually into the bowels of facebook. At least here on the blog the comments are there for people to see in the future.

Now before I want to get some to several of the major critiques regarding plesiosaur spin feeding or the "T-handled socket wrench of death" (thanks Yodelling Cyclist).

As several have pointed out the stomach remains of long necked plesiosaurs consist of relatively small stuff - small squid hooklets, relatively small fish. However I suggest that we be cautious when we construe the diets of animals based on such small sample sizes. We are not getting a complete portrait of what a population or species can do - just an isolated individual and what they ate then and there. And if you look back deep into the literature you find references to bits of pterosaur, small mosasaur, embryonic ichthyosaur, ammonites shell, benthic invertebrates in stomach remains. I do not think we can rule out the idea that some of these critters may have routinely scavenged on large things or even predated good sized things. Let me put it this way I would not go swimming with them no matter how many times small fish are found in their stomach. And lets talk about possible bias in the stomach remains. If you are wrenching off flesh from large animals and assiduously avoiding bones so as not to choke, then those chunks of flesh will not likely fossilize. And with regards to large ammonites we know next to nothing of their soft anatomy, if they had hooklets like many squid do? And finally let us consider modern, opportunistic aquatic predators. Guess what you will find in the vast majority of nile crocodile stomachs if you lavage them? Fish, and mainly small or medium sized ones at that. Or a California sea lion, which is a big predator and can take big fish, what will you find? Mainly small bait fish like sardines and anchovies in the vast majority of stomachs.

All in all I do not think the stomach remains argument is conclusive in plesiosauromorphs being gape-limited predators of small prey. Rather I think the variety of remains found so far is more suggestive of an opportunistic foraging modus operandi.

Another point of contention is the issue of tentacled, suckered prey. What about choking? Eating loads of cephalopods does not seem to cause an issue for sperm whales, pilot whales, beaked whales and other air breathing teuthophages. And again, we do not even know if ammonites had "tentacles" or suckers as we see them on predatory cephalopods today. I have a hunch the less than stream lined, cumbersome and sometimes gigantic ammonites were more passive feeders of plankton, marine snow, and other easily acquired food stuffs. That ammonites were extraordinarily abundant, so much that they are useful index fossils, is consistent with a lower trophic level. And there is at least some evidence to suggest a planktivorous diet.

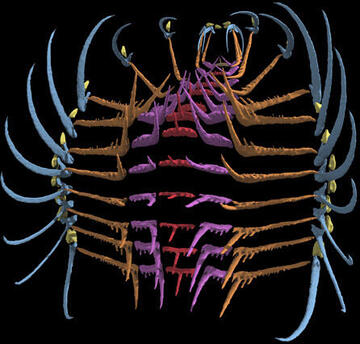

|

| Synchotron Scan of Baculites radula. Each color represents a different "tooth" Tafforeau/Cruta |

Anyways let us look at Mary Anning's original Plesiosaurus dolidocheirus, and see if there are any anatomical clues suggestive of rotational feeding. For starters let us consider the whole body. For an early Jurassic age Plesiosaurus has essentially the basic bauplan all long necked plesiosauromorphs stuck with. One question I have regarding the flippers is: can they be brought back up against the body to achieve a shape more conducive to rolling? Paleoartists draw the flippers in all sorts of ways including up against the body, some think the hind flipper were always pulled back against the body and worked as rudders. I don't know and I have never read of any research looking at the full range of motion for the flippers.

|

| Dmitry Bogdanov |

Now on to the neck, more words have been minced regarding the long necks of these guys than I want or care to go over here. What can be said for certain is that they could not tie their neck in a knot or kink it back in the classic snake like predatory strike look. It is doubtful that the neck was useful in striking at prey at all due to drag, lack of muscle, and if the strike missed it's target the whole animal veered off course because such a long neck acts as essentially a front rudder. And there is good reason that ships are build with the rudder in the back. What can be said for certain regarding these necks and prey capture? That this neck would allow the head to approach prey without betraying the animal's presence via the pressure wave of the body. Of course I believe the neck worked as sort of a fulcrum to allow plesiosauromorphs to wrench ammonites out of their shells but more on that later.

|

| Basic Plesiosaur skull |

Now on to the head and teeth. One persistent semi-myth that seems to stem from the "snake strung the body of a turtle body" is a bit of entrenched notion that plesiosaur skulls were like snakes skulls - light weight struts of bones, kinetic etc etc. Nothing could be further from the truth. The skulls, although small compared to the whole body, are actually quite solid and well put together. That we have a fairly good record of plesiosauromorph skulls, unlike sauropod skulls, is consistent with their solid build. Plesiosaurus itself has a pretty good skull and is noted for an especially strong symphyseal union. From wikipedia: "The two rami of the lower jaw make a "V" shape with an angle of about 45°.[1] The specialized region where they meet, the symphysis, is robust. The two rami are fused at the symphysis, making a pointed, shallow scoop-like shape.[6]"

Now what I want to emphasis here with regards to rotational feeding is the robust symphysis and the "V" shaped angles of the rami in the lower jaw. Both of these are hallmarks for rotational feeding. Rotational feeding places a lot of strain on the symphysis and long narrow jaws (think gharial) are not optimal for the strain of rotational feeding. Rather shorter, stouter jaws are better. A recent paper on rotational feeding in prehistoric crocs said as much. Shorter, stouter snouted Deinosuchus could handle the strain while Sarcosuchus could not.

Why would Plesiosaurus, indeed all long necked plesiosaurs, have these long necks but seemingly blunted skulls?

I would suggest that the skulls were optimized for rotational feeding and there was functional constraints on how long the skulls became. Consider polycotylid plesiosaurs. They have long, narrow gharial like skulls- these were well behaved obligate small prey/piscvorous predators. The long necked plesiosaurs were not well behaved in this manner.

|

| Dolichorhynchops |

|

| Anhinga anhinga. Claudio Dias Timm |

And finally, could the skulls of these guys put up with the mechanical stresses of death rolling? Studies are needed. By people who are better at math/physics than myself. But I have a feeling yes because sushi. What the hell am I talking about? Well essentially it boils down to gravity. Terrestrial critters have big, tough muscle fibers to deal with the strain and effort needed to move about at 1 G. A fish, a squid, an ammonite is not going to have as tough a muscle fiber as a landlubber. That is why people love them some sushi, but eating raw land animals, not so much... so tough and chewy. But some raw tuna meat, the most athletic of fish remember - you can poke a hole through the muscle with your finger.

Support me on Patreon.

Like antediluvian salad on facebook.

Watch me on Deviantart @NashD1.Subscribe to my youtube channel Duane Nash.

My other blog southlandbeaver.blogspot.

4 comments:

"How a flood would wipe out a marine animal?..."

For what it's worth, someone did report how a marine flooding event resulted in a bonebed:

http://www.researchgate.net/publication/257497393_Marine_flooding_event_in_continental_Triassic_facies_identified_by_a_nothosaur_and_placodont_bonebed_(South_Iberian_Paleomargin)

That's extremely interesting anonymous and large typhoon/tsunami would do the trick indeed. How amazing that such a rare phenomena - rarely documented today - entered into the fossil record is astounding thanks for sharing.

Considering what false gharials do, and what with Planista and even Gavialis occasionally eating land animals (two cases of Planista eating large birds and one case of a failed predatory attack on a human by Gavialis), I would not be surprised to find even polycotilids (let alone Plesiosaurus) eating surprisingly large prey.

Scott Mardis - he is a crytpo researcher but also has an encyclopedic knowledge of plesiosaurs - reminded me of this potential evidence of a polycotylid biting a herspernornis: http://saurian.blogspot.com/2012/11/svp-2012-some-tasty-morsels.html

Post a Comment